|

FLY

FISHING IN PROVENCE

Sorgue, Ouvèze and cicadas...

by Tom Mann

*

The top of Mont Ventoux was covered in clouds as I drove

across the Plain of God on my way to the river Ouveze. It was

mid-morning and already hot. I turned off the highway onto a rocky one

lane track between two vineyards. The juicy-looking purple grapes

hanging down from the wires were tempting but I restrained myself. I

parked the car, strung up my rod, donned my Palladium sneakers and my

fishing vest, and paused to look at the water. It is very dry in

Provence this year, but the Ouveze still has some flowing water. Even

though the river flows through farmland for many kilometers, it is rich

in insect life. I turn over some stones and find many nymphs clinging

to them, and the eddies along the banks are covered with a scum of

spent mayfly spinners.

I take a few casts at chevesnes I see swimming in the main current, but

they all see me first and zip madly around the run seeking shelter. The

chevesne is a common European whitefish that is virtually inedible, and

thus manages to survive in France, a land where most of the palatable

creatures--even the songbirds—were long since eaten. Several

years ago, when fate conspired to deposit me in this delightful corner

of the world, where nearly all the local rivers are devoid of trout and

other familiar gamefish, chevesne became the mainstay of my fishing.

They’re spooky but they will take flies readily. Although they

feed constantly under the surface on tiny nymphs and emergers,

they’re best sight-fished with terrestials, including ants,

hoppers, crickets, cicadas, bees and beetles. They will strike

impulsively at the splat of a bug hitting the water. I’ve also

had success using damselfly nymphs in the deeper holes. About 200

meters upstream from the spot where I first entered the Ouveze, I get a

few good shots at some fish holding in a deep pocket under a fallen

tree, and I catch a nice one that turns to inhale my foam ant when it

hits the water. This fish is 40 cm. (16 inches), heavy-bodied and

thick. It doesn’t fight much and swims off quickly when I pull

out the barbless hook.

In the next few days, there are rains in the mountains and the water

levels in the Ouveze rise considerably. This is a good sign, and I make

a note to spend the late afternoon fishing under a Roman bridge in the

nearby town of Vaison la Romaine. On Tuesday morning market days in

Vaison, I always wriggle my way through the crowds of tourists, walk to

the middle of this bridge and look down on the big chevesnes holding in

the fast water below. The last time there were floods in this area,

every bridge over the Ouveze was washed out except this one, built

nearly two thousand years ago by the Romans. They wisely sited the

bridge where it could be anchored solidly on both ends in rock

formations. Later in the day, I park by the river in downtown Vaison,

rig up my rod, and walk out on the smooth light-colored stones under

the Roman Bridge. The water is very shallow here, except for a deep

channel under the bridge. I drift a damselfly nymph in front of the

biggest chevesnes holding in the current. One takes it and I strike.

The fish thrashes about, but I drag it up onto the wide shallow part of

the river bed and it immediately gives up the struggle, and lies there

waiting for me to unhook it. I repeat this routine several times. These

French fish really go for les demoiselles. Were there pods of brown

trout waiting to be caught in this same run, before the Romans fished

them out? I go home feeling satisfied, even if the fish were lowly,

inedible chevesnes.

The chilly river Sorgue is the only prime trout stream in the hot, dry

Mediterranean climate of Provence, and it also has the southernmost

population of grayling in Europe. It gushes out of a deep fissure under

the mountains in the picturesque town of Fontaine de Vaucluse. Not even

Jacques Cousteau could locate its underground source. Seven kilometers

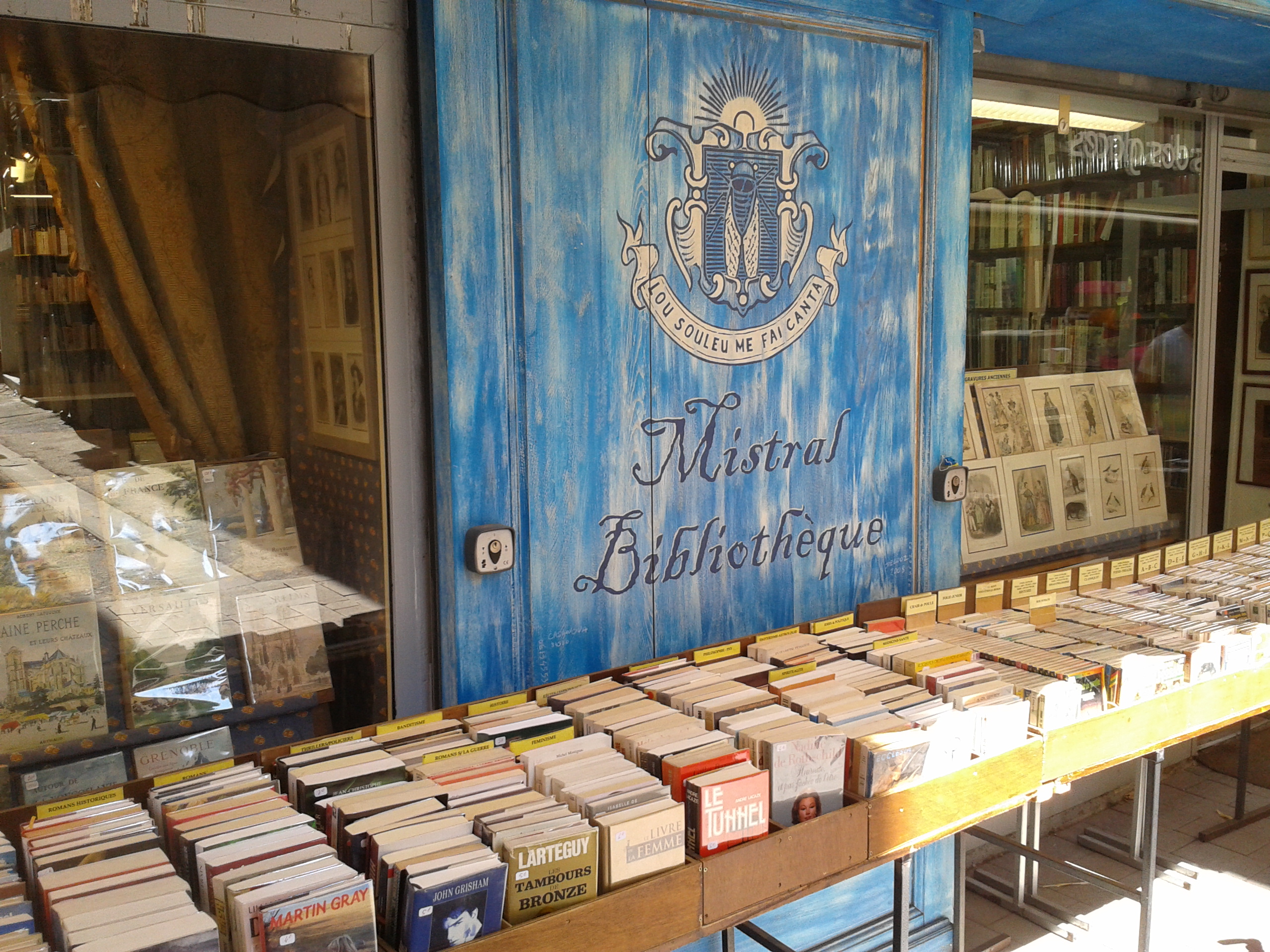

downstream from Fontaine de Vaucluse, the Sorgue flows through the town

of L’Isle sur la Sorgue, a center for tourism and antiques with a

popular Sunday street market. It is an understatement to say that the

Sorgue is hard to fish. Our American ways of casting like a poster

person for A River Runs Through It just don’t work in it, despite

the presence of mayflies, caddisflies, and scads of scuds and

cressbugs. I tried to catch a trout in the Sorgue’s icy waters

for years without success, a fate shared by several famous American

anglers who will remain nameless. A senior French fly fisherman who

makes fishing vests tells me that fishing in “the Montana”

is like catching ducks in a barrel, and that we Americans are used to

trout that are too easy to fool. Good-naturedly, his son reminds me

that the French team won the 1998 world championship of fly fishing

when it was held in Big Sky Country. Once you admit defeat, the local

fly fishermen are willing to help you crack the secrets of the Sorgue.

The technique that works there is “dapping,” done by

dangling a weighted nymph (or a dry fly when there is a hatch on) in

front of a fish’s nose on a short line (a long leader tapered

down to 7X) with a ten foot rod. You watch the fish, and if it moves,

you strike. I have seen this technique work, and next year, I will try

again to catch a trout in the Sorgue.

Courtesy of Tom Mann for Gourmetfly.com. All rights

reserved. Tom is a keen American

writer and fly fisherman sharing

his time between Montana and Provence...

|